by Asia Leonardi for the Carl Kruse Blog

How much does it cost to be a woman?

Before you turn your nose at the question, I make it clear that the choice of words is deliberate. The cost of

being a woman is higher than that of a man. And I’m not talking about battles for inclusion or mere sophistries about the poetry of female sensibility. I am talking about facts, statistics: during her life, a woman spends much more money than a man to meet her needs. And not only: the Pink Tax is a very common price increase that applies to the vast majority of products dedicated to women. It is a phenomenon that is explained according to the premise of supply and demand. That is to say, if demand exceeds supply, the cost of the product increases. The Pink Tax was born from a cultural stereotype that dates back to the first age of consumerism, the fifties: the woman spends her free time spending money that she does not earn. Tampons, makeup, perfumes, face creams: these are just some of the products that present the Pink Tax. But it is not an isolated phenomenon: just think of the Tampon Tax, for example, that is to say, the taxation on tampons and nappies branded as ordinary goods, or the Gender Pay Gap, that is, the wage imbalance according to which women are paid less than men, even if they work in the same position.

Being a woman is not a luxury. As a woman, if I had a good job, I wouldn’t be surprised if someone would make a joke of me asking who I slept with to earn it. As a woman, it’s no wonder that someone, even if I am not showing consent, is harassing me. As a woman, if I’m nervous, no wonder someone asks me if I’m having my period.

Being a woman is not a luxury, it is not a privilege. I do not want to enter into a feminist debate; I prefer to make history speak. I prefer to make speak the voice of a word, which over the centuries has been imbued with prejudice, misogyny, pseudo-science: hysteria. The combination of woman-hysteria is still a cliché, a stereotype that hides years of patriarchal despotism, whispers that have been imprisoned in a fictitious disease whose sole purpose was to pathologize the female condition.

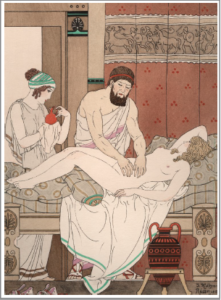

It is no coincidence that the word “hysteria” comes from the Greek “hysterion”, which means “uterus”. The Greek doctor Hippocrates, in his Corpus Hippocraticum, says that “the uterus is the cause of all the diseases of women”. According to the ancient theory, the uterine organ, dry and hollow, absorbs a high amount of substances that is forced to expel in the form of menstrual blood. The woman would need male coitus just to balance the differences in moisture in the uterus.

Joseph Kuhn Regnier, “The Works of Hippocrates”, 1924

When this does not happen, the woman suffers and experiences the so-called “hysterical suffocation”, that is, a condition of suffocation and mental confusion. We can certainly not conclude that Hippocrates’ intentions concealed the desire to stigmatize the condition of women; However, his assertions, taken as cast gold, were later misunderstood and instrumentalized. The woman, if she can’t find a man to sleep with, becomes hysterical.

Let’s just skip ahead to the fanatical phenomenon of the “witch hunt”, typically medieval but lasting until the seventeenth century, associated with the figure of the witch, scapegoat of a greater evil, as a figure affected by female hysteria, whose symptoms were explained by the demon’s possession of her body. The basis of this theory was the publication, in 1486, of the Malleus Maleficarum, (literally “The Hammer of Witches”) written by the Dominican preachers Heinrich Institor Kramer and Jacob Sprenger.

According to the Church, it was because of the sinful and fickle nature of the first woman, Eve, that man fell into the abuse of evil. And it is precisely in the vortex of female lust that Sprenger and Kramer pursue the despicable figure of the woman in every manifestation. Women are naturally wicked, cruel, and deceitful, ruled by animal instincts and therefore much more sensitive to welcome in them the presence of the devil. The unmistakable mark of the witch is her sex, as the Bible says in Proverbs: the mouth of the uterus is never satisfied….their face is a burning wind, and their voice is the hissing of a serpent… Their heart is a net, that is, inscrutable is the wickedness that reigns in their hearts and… an insatiable thing that never says enough: the mouth of the vulva for which they agitate with the devils to satisfy their lust. (Institor Kramer, H. – Sprenger, J. Malleus Maleficarum, p. 95, Spirale, Milano, 2006).

Only in 1656, with the opening of the Salpêtrière in Paris, a hospital that, disguised as charity work,

was a madhouse where the society ’s outcasts were interned, the illustrious director Philippe Pinel modified the approach to the disease by abolishing torture, chains, and exorcisms.

During the Victorian era (1837-1901), positivist culture radicalized gender roles as a natural representation: the woman is the “angel of the hearth”, must devote herself to the home, to the education of children, neither social nor civil rights belong to her, and cannot own a property. She, on the contrary, was a property: first of the father, then of the husband. In petitions for universal suffrage, women were not included: only those who, culturally and economically, were able to make a choice had the right to vote, and it was an established and socially accepted belief that it was enough for the man to express the vote of the family, The woman was subordinate to her husband, completely dependent on him and would not have been able to express her independent opinion, also because she was considered too unstable to participate in political life. The female gender, moreover, still felt the stylistic influences of the “angel woman”, a modest being, fragile and pure, whose body was a sacred temple, which could not be violated, neither by physical efforts nor by sexual practice. The man, the pater familias, had the task of protecting the delicate being, preserving the dignity of the family name, instructing and educating it, very

often with the use of violence.

A Procession of Flagellants, Goya, 1812

With the advancement of medical science, it was precisely at the Salpêtriere hospital that Sigmund Freud began his career, and, in his “Studies on hysteria”, referred hysterical disease to the repression of sexual desire, definitively eliminating the theory of the errant uterus. However, despite Freud’s research focusing on patients of both sexes, he inferred that it was a purely female disorder so that the repression of desire was traced back to the role of women in society, alone and bored at home, While the man works with commitment and dedication, he returns home tired and devotes little interest to his wife.

In 1847, Charlotte Brontë wrote some unforgettable pages about the limited role of the woman,placing them in the voice of Jane Eyre:Women are supposed to be very calm generally: but women feel just as men feel; they need exercise for their faculties and a field for their efforts as much as their brothers do; they suffer from too rigid a restraint, too absolute a stagnation, precisely as men would suffer; and it is narrow-minded in their more privileged fellow-creatures to say that they ought to confine themselves to making puddings and knitting stockings, to playing on the piano and embroidering bags. (ch. 12) However, despite the abandonment of the biological causes of hysteria, nineteenth-century psychiatrists continued to practice the technique of “hysterical paroxysm” on patients who showed symptoms attributable to hysteria. This barbaric practice consisted of clitoral or vaginal stimulation to lead the woman to orgasm, not recognized as the apex of pleasure, since it was a common belief that the woman was not able to feel pleasure.

Many women were prescribed the “rest cure”: they were segregated at home, in bed, with the strict prohibition to engage in any activity, devoid of any stimulus for months. The psychiatrist that developed the “rest cure” was Silas Weir Mitchell. He, at least, was honest about the punitive function of this treatment for all the women that didn’t show the will to collaborate.

The rest I like for [female invalids] is not at all their notion of rest. To lie abed half the day, and sew a little and read a little, and be interesting and excite sympathy, is all very well, but when they are bidden to stay in bed a month, and neither to read, write, nor sew, and to have one nurse, – who is not a relative – then rest becomes for some women a rather bitter medicine, and they are glad enough to accept the order to rise and go about.

(from “Fat and Blood”, 43, 1884, S. W. Mitchell)

The highly autobiographical tale of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, “The Yellow Wallpaper“,

published in 1892, is unforgettable. Presented in diary form, Charlotte Perkins Gilman tells the

story of a young woman struggling with a “rest cure” prescribed by her doctor husband to treat

what he calls a “temporary nervous depression”, highlighting the elegantly disguised constraints that oppressed women in the Victorian era. The woman in the story is confined to a summer residence, where, in the bedroom, she is immediately struck by the bright color and recurring motifs of the wallpaper. Confined, without the possibility of dedicating herself to any activity, the protagonist carefully studies the wallpaper, which has become the alibi of her frustrations, until she sees a woman trapped in the design, who crawls and cannot free herself.

Time passes, the paranoia of the woman grows, and in her comes the obsessive desire to free the woman from her prison, and unconsciously, to free even herself. So, on the last day of her stay in the mansion, she locks herself in the bedroom and rips the wallpaper. When the husband manages to enter the room, and wonders what’s happened, she exclaims: “I’ve got out at last, in spite of you and Jane. And I’ve pulled off most of the paper, so you can’t pull me back!”

The prejudice of the woman driven by “hormones and mysterious instincts” still survives today. We are all sensitive to hormonal changes, some know how to manage them and others are most influenced by them, however, the common belief still often sees the woman overwhelmed in a vortex whose only horizon is marked by unpredictability and irrationality. When a woman expresses her torment, her suffering, or her nervousness, it is common to think that she is exaggerating, unwittingly conducted in a hormonal fury that will soon pass by and therefore does not need to take seriously. The woman’s pain was reduced to a mysterious and unknowable suggestion, for a long time brought back to the female psyche, ineluctably connected to her uterus. Even today, many women who suffer from reproductive diseases, are told that they have invented everything and that their pain is simply a construction in their heads.

Perhaps, today, we might recognize at times the vein of female rebellion in the photos of Cécile Hoodie. Little is known about her, but as she says, her photographs seem to have come directly from the film The Virgin Suicides by Sophie Coppola, based on the novel of the same name by Jeffrey Eugenides. Cécile’s photos are loaded with a provocative fire, camouflaged as symbols such as glitter, makeup, tampons, chewing gum, and dig into hot topics such as sex, drugs, violence, alienation, suffering, and torment of teenage girls struggling with their first love experiences. In the present icons, in the most common gestures, in-jokes and not, are hidden centuries of history, repression, discrimination, and stereotypes Sometimes words are not enough, they are not listened to, some people twist their nose to hear the word “feminism” coming out of a woman’s mouth. This is how photographs, statistics, and history are used: sad to say but, when the female voice becomes impersonal, the audience begins to listen.

================

This Carl Kruse Blog homepage is at https://carlkruse.at

Contact: carl AT carlkruse DOT com

Other articles by Asia include: Highrise, An Appreciation of the Map, and On the Consolation of Psychedelics.

Find Carl Kruse also on two of his older blogs: Carl Kruse Old Blog 1 and Carl Kruse Old Blog 2.